معلومات عنا

دعم العملاء

احصل على التطبيق

قم بتوجيه الكاميرا لتنزيل التطبيق

حقوق الطبع والنشر © 2024 Desertcart Holdings Limited

Full description not available

I**N

There are secrets that philosophers hide from the masses

The ancient Greeks were the first people who wrote about philosophy and the greatest of these Greeks were Plato (428/427-348/347 BCE) and Aristotle (384-322). They wrote in Greek, and since many later people did not know Greek, if it were not for Islamic writers who knew Greek and who translated their writings into Arabic, Jews and Christians would have had no knowledge of these great men or of philosophy. One of first of these Islamic writers was Alfarabi (870-950). Alfarabi tells us that Plato could not reveal the truth to everyone because they would not understand it and would feel threatened by ideas that conflict with what they felt was true:The wise Plato did not feel free to reveal and uncover every kind of knowledge for all people. Therefore he followed the practice of using symbols, riddles, obscurity, and difficulty, so that knowledge would not fall into the hands of those who do not deserve it and be deformed, or into the hands of someone who does not know its worth or who uses it improperly. In this he was right.Thus, Alfarabi, Muhsin Mahdi writes, also hid the truth from the general population by brazenly using "self-contradiction - between works, between passages, and even, at least once, within the same sentence. The uses of this device are manifold."Alfarabi states that one of these truths, in fact the basic truth that Plato could not teach the general population, is that spending one's life developing one's mind is the only true fulfillment of human existence. The thinking must focus on the practical and political, the sciences that benefit the individual and society. This knowledge can only be obtained by associating and cooperating with others and living next to them.Plato, Alfarabi writes, was not speaking of religious knowledge, another idea that the general population could not accept. Religious thinking "is not sufficient." "Religion is "an imitation of philosophy." It supplies an imaginative unexamined account of nature that the general population needs to know, but not the truth. But the perfect person, according to Plato, is one who learns the real truth and lives a life that reflects it. This was the problem faced by Plato's teacher:For when he [Socrates] knew that he could not survive except by conforming to false opinions and leading a base way of life, he preferred death to life. Aristotle, Plato's student, Alfarabi wrote, had the same understanding as Plato "and more." Aristotle investigated and described the causes of everything that he could see and think about, practical and theoretical science. He examined the purpose of everything by looking at all of its parts. He divided what he found into classes. He gave an account of all he saw. He spoke of logic, drama, poetry, and other subjects and described how they should work. Alfarabi portrays Aristotle as taking some of Plato's ideas, as well as others that Plato did not discuss, and examining them as a scientist would probe them today. Thus, for example, while Plato speaks about the soul, Aristotle defines it as the various parts of the body, such as the nutritive and respiratory systems that keep the body alive, as well as the intellect. This intellect is the true and only aspect of humans that differentiates them from animals and inanimate objects. Thus people who do not develop their intellect have failed to become truly human. All the parts of the soul die with the body, except for the intellect, but Aristotle seems to say that this surviving intellect has no recollection of its prior life. Aristotle's view of the soul is another philosophical teaching that would disturb the general population.

A**A

Great book

Great book

J**N

Who was al-Farabi?

Alfarabi is one of the greatest philosophers to walk the earth since Plato and Aristotle left the sublunary world! This must seem an outrageous statement given how little Farabi is read, taught, or even translated here in the West. But what we today do not realize is: first, how Farabi defined the limits of medieval thought and, secondly, how those limits became part of the modern world. In this note I would like to start out by giving a brief indication of this.Farabi is the first philosopher (that we know of) to notice that the world that philosophy inhabited was no longer the 'natural cave' that Plato spoke of in the Republic. Today, thanks to our reading of Nietzsche, it is almost a commonplace to refer to Christianity (and also, by extension, Islam, Liberalism and Socialism) as a 'Platonism for the people'. Farabi, by realizing that philosophy had in his time become lost (or forgotten), decisively leaves the ancient world (i.e., the natural cave) behind and enters, whether cheerfully, fearfully or cautiously we will never know, a world (specifically, the world of medieval monotheism) in which the shadows on the wall of the cave are no longer simply those thrown by 'natural', that is, pre-philosophical, customary religion and law (i.e., nomos); but rather these shadows are now (since the rise of the first 'Platonism for the people') -at least in part and in varying degrees- philosophical artifacts. So, how does philosophy behave once a (ahem) philosophical 'theory of everything' arises? That was the question that Farabi faced; and that was a question neither Plato nor Aristotle ever faced...Now, philosophical esotericism in Antiquity was always concerned with the individual; it ultimately wanted to free the individual from his thralldom to nomos or sophistry and bring him to philosophy. But Farabi faces a situation in which everyone (i.e., the Christians and Moslems of his time) already knows the Truth and has God on their side. Farabi must establish and defend the continued necessary existence of philosophy in the face of an all-knowing, all-powerful God. After all, why would those who possess a Revelation search for Truth when it is here, in front of them, in the 'Religion of our People'? Farabi's "Philosophy of Plato and Aristotle" demonstrates the great skepticism genuine Philosophy has for Truth and the self-assured (but ultimately sophistical) holders of Truth by, in part, resorting to (or inventing) Platonic political esotericism.In order to counteract the 'strong' illusions on the walls of this cave (i.e., monotheism) Farabi proposes, in the 'Attainment of Happiness', a fidelity to method that is (perhaps) unprecedented in the ancient world. This fidelity to method, of course, is intended, as Farabi indicates, to ensure a singularity of outcomes. (Fundamentally, Descartes will later use method for the same reason.) Now, the fact that the 'school' Farabi heads (the Islamic Philosophers, - that is, the Falasifa) disappears down the gullet of history is no reason to think that the story ended there. Averroes who, for the purposes of this brief note, can be identified as the last of the great 'Aristotelian' Falasifa, had an immense, but subterranean, impact on Western philosophy. Indeed, after Aquinas lost the good fight for a (moderate) 'Latin Aristotelianism', a 'radical Averroism' would eventually triumph in the West. (This 'Averroism', however, was in fact blind to the 'religious philosophy' of Averroes, that is, they had never seen his 'Decisive Treatise', and therefore went too far in the direction of secularism.) Before the rise of this 'Latin Averroism', however, a form of Kalam (Islamic Speculative Theology) would rule the Western world. But eventually this anti-rational, 'God's Will' theology of Scotus and Ockham is overthrown by the new secular philosophies best represented by Machiavelli, Descartes, Hobbes and Spinoza. These last are the genuine, but by no means merely direct, heirs of radical Latin Averroism. And this early-modern secularism eventually became the modern Enlightenment which continues its transformation of the world even today. But post-modernity is only the latest skirmish in the 'jihad of the falasifa' which may have ultimately begun, however much it has changed over time, in the thought of one man - Farabi.Farabi changes Philosophy because the world that philosophy inhabited had irrevocably changed. The merely customary Nomos of classical antiquity was replaced by Revealed Law. But why was that a problem? Hadn't philosophy itself a hand in the rise of the monotheistic 'Platonisms for the People'? Yes, philosophy did have a hand in it. (Now, whether Plato intended to remake the world in this manner is another question, one which I will not address here.) But it is only too obvious that the various (at best) squabbling or (at worse) warring factions among the monotheists (Christianity/Islam, Catholic/Orthodox, Sunni/Shia, e.g.) were certainly not intended by the philosophers. This is, in part, the reason behind the great innovation of the 'Attainment of Happiness': Farabi teaches that one method, not one Truth, leads to one result. This single-minded pursuit of a single behavior is intended to moderate, and eventually end, the countless internecine conflicts of the various monotheistic sects.Where the ancient philosophical schools had always practiced some form of 'soulcraft' on their students Farabi only wants to elicit a common, and therefore 'correct', behavior. The ancient study of philosophy generally culminated in some sort of truth. Of course, a given student might never reach the culminating truth. But the practice of philosophical soulcraft would, or so it was hoped, improve any student. Before Farabi philosophy always at least attempted to address the soul or psyche of individuals; after him, and to an ever increasing degree, philosophy addresses behavior by teaching one method, and philosophy thus purposefully addresses World-History; that is, philosophy is from this point on self-consciously making the future...Now, this book is a tryptich, it begins with 'Attainment of Happiness', it has 'The Philosophy of Plato' in the middle, and it ends with 'The Philosophy of Aristotle'. We are to understand that the 'Attainment of Happiness' is Farabi's original contribution to Philosophy. This book was, in medieval times, referred to as 'The Two Philosophers'; in reality it could have been (and indeed should have been) referred to as the 'Three Philosophers'. - I mean by this that, according to our author, after Plato & Aristotle there is only Farabi. I recommend reading the book first in the traditional order: Farabi, Plato, Aristotle, and then reading it in chronological order, Plato, Aristotle, Farabi; and finally, reverse the chronological order, Farabi, Aristotle, Plato. This last, btw, has the virtue of allowing one to view the history of philosophy as Farabi himself saw it: that is, himself, Aristotle, Plato.But reading this book chronologically, from Plato to Farabi, also has its merits. So we begin with Plato. Farabi, swimming in the wake of the results of Platonic esoteric caution, exaggerates the importance of Politics in his explication of Plato in order to counteract the even greater incaution of Revealed Religious Law. It is, unfortunately, often necessary to counter one exaggeration with another. In a storm (and History, may the gods help us, is a storm!) one always finds oneself steering in this, that and/or some other direction in order to simply stay on course. Farabi, towards the end of the `Philosophy of Plato', alludes to the methods and ways of Timaeus, Socrates and Thrasymachus. These three are masks (or signs) of the three fundamental things the philosopher can speak about: Cosmos (or Theology), the individual Soul or Psyche, and the City (or Politics). Philosophy, in Itself, can perhaps be defined as the mixture of these three ways, in their proper measure at the proper time. I leave it to the discerning reader of the `Philosophy of Plato' to determine which of these three ways Farabi elects to emphasize here. Keep in mind that in another work, for instance "On the Perfect State", Farabi may well choose to proceed in a (somewhat, if not entirely) different manner...You should see the criticism of other philosophers inherent in the way Farabi here discusses Plato: Thus the ways of some other ancient philosophers (e.g., Parmenides or Pythagoras) would then be, from the viewpoint of Plato, or perhaps I should say the 'Plato' of Farabi, an immoderate privileging of the 'way of Timaeus'. Another point to note is that of these three (i.e., Cosmos, City, Soul) the only one that the philosopher can fundamentally effect is the City. This is simultaneously a great danger and (perhaps) an even greater opportunity. In either case, it should really surprise no one that philosophy winds up here, in our post-modernity, thinking it has made (or will make) everything in the City... I want to add that for those who continue to insist upon the alleged 'Neoplatonism' of Farabi this essay, 'The Philosophy of Plato', must always remain a great scandal to them. We should never stop being amazed by the fact that in this essay Farabi can't even bring himself to mention the Platonic Ideas! As an aside I will point out that this can also be said of the 'Platonist' (really, the Farabian) Leo Strauss. In fact it has been said, by one of the greatest students of Strauss - Stanley Rosen. Now, Rosen isn't at all happy about this but this unhappiness is the result of his expecting Strauss to behave like a Platonist when Strauss is in fact a Farabian. Well, enough of this digression...Regarding Aristotle I can only mention, in these brief remarks, that just as Farabi's Plato barely discusses 'Metaphysics' so too Farabi's Aristotle barely discusses politics. Farabi says Plato's discussion terminates (i.e., finishes) but near the very end of the Aristotle essay Farabi says "we do not possess metaphysical science." One can perhaps understand this to mean that, properly speaking, 'metaphysical" investigation is endless while Plato, in fact, exhausted the study of philosophical anthropology and politics. In closing I should say that in order to properly understand the philosophy of Farabi (i.e.,"The Attainment of Happiness") we need to see how he intends to utilize the results of Plato's investigations in order to secure foundations that support unending metaphysical research. The 'Attainment of Happiness' ends with Farabi assuring us that Plato and Aristotle "intended to offer one and the same philosophy." We should add that this was Farabi's intention too.Farabi is the least read of the great philosophers. Begin your study here.

M**B

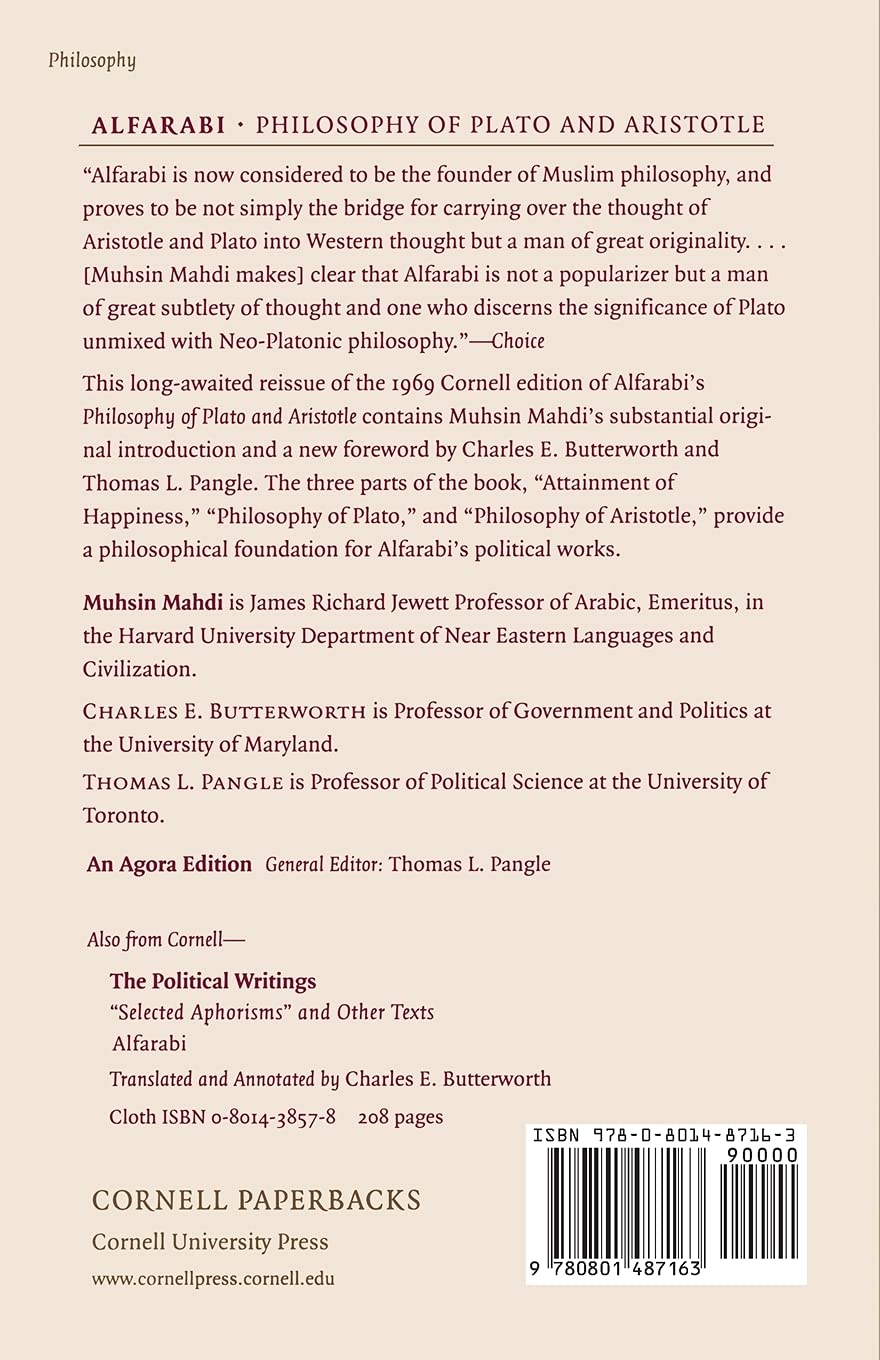

Philosophy of plato and aristotle: alfarabi

While some would consider al-Kindi as being the first Muslim philosopher, others would consider AlFarabi as the founder of Muslim philosophy; a parallel clearly with the way Plato and Aristotle are considered in the context of the development of western philosophy. That said, AlFarabi was a prodigious translator of Greek texts into Arabic, not only providing access to texts by Plato, Aristotle, and some of the Neoplatonists, but also people like pseudo-Dionysius, whose Arabic translation was translated into Latin well before the west had access to the original Greek.This book is essentially in three parts: ‘The attainment of happiness’, ‘The Philosophy of Plato’, and the ‘Philosophy of Aristotle.’ ‘The attainment of happiness’ I found to be a brilliant example of inductive reasoning, albeit on the long side, and probably a lot closer to Aristotle in approach, than Plato (the same might also be said of the scholastics), and a total contrast in the approach taken to the same subject by Ghazali. The orientation is political in the same sense that the Republic is political, but at its heart is the establishment of virtue. The section on Plato, is a brilliantly concise overview of a large selection of dialogues from Plato’s oeuvre, drawing connections between dialogues which might have missed the attention of a less acute mind. The section on Aristotle is about twice the length of the former, which suggests a predisposition, hardly surprising perhaps given AlFarabi’s interest in political philosophy as contrasted with writers such as Averroes and Avicenna. This is not a big book, only some 130 pages plus very extensive notes, but for a different perspective on both Plato and Aristotle, it is to be welcomed.

ترست بايلوت

منذ أسبوعين

منذ 3 أسابيع