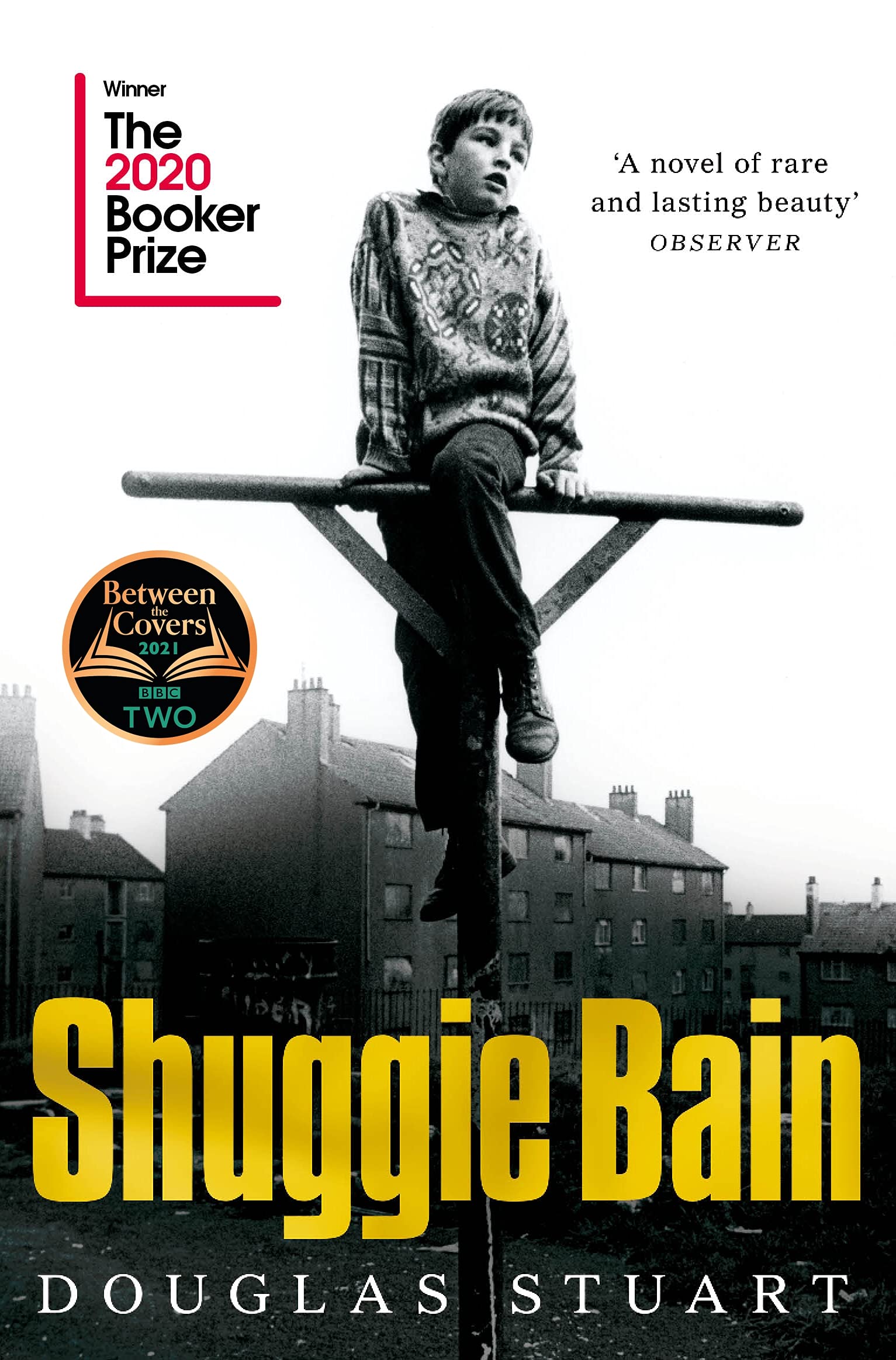

Shuggie Bain: The Million-Copy Bestseller & Winner of the Booker Prize

G**N

brilliant

Absolutely loved reading this book. Devastatingly sad and heartbreakingly hopeful. Soaked in nostalgia, it tells of a life of unthinkable struggle , that is hard to imagine any child having to deal with but written so beautifully , in sharp contrast to its subject matter . I did not want it to end.

S**E

The Grit Of Poverty.

This superb story is essentially in three parts. In the first and final parts we encounter Shuggie after he has physically escaped the events of the lengthy middle portion. I thought the first part was too long and caused a wrench when the book stepped back ten years, moving into the second section, taking Shuggie back to his childhood, especially as the reader really needed some knowledge of the main events in order to process this first section. This is a minor complaint; the author picks us up and carries us along once we meet Shuggie's family.The bulk of the main story concerns Shuggie's mother, Agnes, an alcoholic struggling - and struggling is the word - to control her alcoholism, bring up three children, experience some sort of life, realise her hopes and ambitions, and negotiate the people around her. Her love for her kids is manifest but she and they are doomed by drink, feckless lovers, vicious neighbours and an absence of any true friends. She meets a man she likes but even he - actually one of the more decent characters - betrays her in the most convincing and destructive manner.Agnes herself is superbly drawn - her alcoholism-cycle of drink, stupor, guilt, drink again, and her changes in character from sweet and loving, through drunken rage and spite to hungover regret are utterly true to life: one alcoholic possesses several conflicting personalities.The author has set the novel in eighties Scotland and hints at the damage done by Margaret Thatcher's government to Agnes' neighbourhood, employment prospects and class, but doesn't ram Thatcher down the reader's throat. This is just as well because it is one component of the social environment in which Shuggie's family try to live. Agnes' ambitions to rise out of her poverty and degradation are thwarted time and again by her alcoholism, uncaring - even absent- local and national governments, and by a cold society isolating and degrading her and her family. Logically, this vile environment did not just spring up with the new government; it had been festering for years. Agnes didn't have a chance. In the middle of this mess we find Shuggie, a decent, seemingly doomed boy striving to cope with and care for his loving but incapable and deteriorating mother as well as negotiate both his emerging sexuality and the pitfalls of simply growing up. The warmth of his mother, and her guilt over his plight, the convincingly well masked affection of his brother, are clearly drawn in description as well as appropriately gritty language. I felt I was listening to the authentic voice of deprived and struggling Glaswegians.The landscape and emotional life of the book are stark and bleak but the superb quality of the prose carries the reader through to the final section. This is a narrative novel not a trite story with a message. It does, I think, have a kernel of redemptive seed to it. Three quarters through, Shuggie goes to cash a benefit book for his mother. The regulation-spouting cashier considers refusing to oblige but eventually pays up when the queue becomes impatient. As she does so, she dispenses a few words of wisdom representing the only real hope Shuggie ,or any of us, really has. It's a crucial scene, all the more poignant because the cashier - however distantly - represents callous officialdom.Towards the end there is a tragicomic development when an acquaintance invites Shuggie along to makeup numbers on a date (of sorts!) A beam of hope under a louring Glasgow sky. Is the hope realised? I won't spoil it.Shuggie Bain deserves its place in the short list. I wish it well for the award.

A**M

A Worthy Winner of the Booker Prize?

Ostensibly the story of an effeminate, hard-done-by lad named Shuggie growing up in rough and tough Glasgow during the Thatcher era, Shuggie Bain is really an homage to his alcoholic mother Agnes.This book saw me plunge into a grim mood. The message I took from Shuggie Bain was that men are brutes… And women aren’t much better. Except for Shuggie and Agnes, of course, who are loosely based on the author Douglas Stuart and his mother. “It’s not a memoir,” Stuart told The Scotsman, “and it’s not strictly autobiographical, but I definitely grew up incredibly poor, raised on benefits, and I am the queer son of a single mother who lost her own battle with alcoholism when I was still in high school.” As a result, Stuart always paints Agnes lovingly, and Shuggie too.There is much to admire about this debut novel. Shuggie Bain is brimming with rich description and creditably tells the story of an underclass that has seldom been represented so affectionately in respectable British literature since Dickens. The plot is crystal clear as one horror follows another with barely any reprieve. The characters are well-drawn. The dialogue, replete with Glaswegian vernacular, is plausible and often humorous.It opens in 1992 and depicts 16-year-old Shuggie’s piteous poverty. He works in a supermarket and lives in a bedsit. He spends his mornings defending himself against the cold and the keyhole-peering predations of older men: “Shuggie could feel it burn into his pale chest as the man’s gaze slid down over his loose underwear to his bare legs”. I question whether opening the novel in 1992 in order to flashback to 1981 was necessary. Draughts and pervy older drunks are gritty, but by unveiling—or undressing—the teenaged Shuggie, the prologue unintentionally immunised the reader from the hardships Shuggie was to face later (or, you might say, earlier). In particular, I felt the opening diminished the impact of what ought to have been a harrowing moment when the younger Shuggie inevitably—such was the trajectory of this novel—got sexually assaulted. However, take away the opening section and the switch back in time and there would be nothing particularly innovative in terms of structure or form.Michael Delgado points out another criticism in the Literary Review: “Stuart never fully settles on a coherent narrative voice. [...] It’s hard to believe that Shuggie’s abusive father would look out at George Square and think of ‘the city at peace, before it got ruined by the diurnal masses’.” The inability to settle on a clear narrative point of view hampers the book fundamentally. Because the novel is not about Shuggie nor entirely about Agnes either, the author feels at liberty to narrate offshoots of other lives. From Shuggie’s siblings to Agnes’s parents, it feels as if half the inhabitants of Glasgow get a chapter to themselves. The result is that the book is overlong: 400 pages feels like 600.Understandably, given that Stuart is writing from lived experiences, the depiction of Glasgow, replete with tower blocks, motorway bridges and a monumental slag heap, is what Scots might call “dreich” (dull or gloomy). The novel captures the drudgery and the trauma of working-class life all too well. Something dreadful happens in almost every chapter—arson, knife crime, corporal punishment of a 39-year-old woman, rape, death by cancer, death by suicide, fighting, more rape, attempted suicide. Perhaps Stuart was making the point that living with an alcoholic mother, an absent father and vile surroundings is predictable only insofar as every day is guaranteed to bring new unpredictable horrors.As a gay reader only too accustomed to bleak LGBT coming-of-age stories, I agree with booktuber Matthew Sciarappa that this book would have felt more timely ten years ago or more. It would have made a startling working-class counterpoint to the gay protagonist’s London high life in Alan Hollinghurst’s The Line of Beauty, similarly set in the 1980s, which won the Booker Prize in 2004. Was this 2020 novel, from a Scottish New Yorker, supposed to make LGBT readers grateful for how far society has come? Perhaps.This year, four debut novels including Shuggie Bain were shortlisted, after the Booker Prize judges inexcusably shunted aside Hilary Mantel’s The Mirror & the Light, without doubt the most accomplished novel on the longlist. As I said when the shortlist was revealed, despite its problems Shuggie Bain was one of the best books left in a competition that in the last couple of years has become, regrettably, little more than an overhyped celebration of popular fiction.

B**R

Surviving in an Unsympathetic World

It is a long time since a novel has had such a profound effect on me. The book tells the story of a boy’s childhood and teen years in the rather rough-and-tumble world of Glasgow in the 1970s and 1980s. Shuggie grows up in a grim, lower-class environment, in which the ordinary difficulties of life are magnified by the unemployment and economic woes brought on by the policies of Margaret Thatcher. Despite his intelligence, Shuggie senses that he is “different” without fully understanding how or why. His dysfunctional family consists of a dissolute father, who soon abandons the family, a step-brother and step-sister neither of whom is particularly close to him, and his mother to whom he is absolutely devoted. Unfortunately, his mother is also an alcoholic and her disease provides the prime motivation for the events of the novel. It would be incorrect to say that I “enjoyed” the novel for it is hard to enjoy such a tale of unrelieved woe. Shuggie’s attempts to deal with the problems of his family while simultaneously surviving in an unsympathetic and occasionally violent world are heart-wrenching. The author’s skill at recreating the events of Shuggie’s life and at capturing the atmosphere of the era (in, at times, a wonderful Scottish dialect) make this an unforgettable read.

A**S

Warming,Emotional,Tenacious

The Book beautifully depicts the scenario of 90’s Glasgow. It is a warming book about a never-give-up relationship between a mother and a son. How far can Shuggie go for his alcoholic mother to provide a better life for her? Penned down exquisitely by Stuart

N**I

A fantastic read, nothing new, but beatufilly written

I really liked the book and I recommend it to everyone. The story is nothing new, alcoholic mother with gay son, but it's written in a fantastic, incredible way. Some chapters are pule style, you will always remember them. Maybe with 100 less pages it would have been more perfect, but you will never regret reaing this book.

A**E

An unforgettable book

An absolutely brilliantly written book set in Glasgow in the 80's about a son's relationship with his addict mother. It made me cry and laugh, the portrayal of poverty, abuse and addiction told through the eyes of a child is heartbreaking

H**R

"He clung to her like a limpet..."

Behold, the heart of Shuggie Bain, Douglas Stuart’s ’s achingly beautiful 2020 debut of the same name. Glasgow’s young Shuggie, who “wasn’t really one or the other”--Catholic or Protestant, boy or man, right or “no right”--is nonetheless fastidiously loyal to his alcoholic mammy. Twice-divorced Agnes Bain can initially hide the wreckage of “the drink.” Vibrant, well-spoken, and pretty, at first Agnes doesn’t show lines on her face, water in her eyes: “Every day with the makeup on...she climbed out of her grave and held her head high...put on her best coat, and faced the world. When her belly was empty and her weans were hungry, she did her hair and let the world think otherwise.”Neighbors gossip and teachers fret, but really, “no one sees the flying woman.” Everyone leaves her: Agnes’ husbands and lovers, her daughter, her son. But Shuggie sees her. He’ll never leave. “I’d do anything for you,” he tells Agnes, when she trades buying him food for more of her drink.After one too many lagers unravels Agnes’ life like the “toe to waist” run in her Pretty Pollys, though, Shuggie—having devoted his school days to buying her lager with food money, putting her to bed, and believing her promises to “give up the drink” and “get a job like other mammies”—wonders, “Why can’t I be enough?”Every child of an alcoholic has asked herself that question. And if anything were ever enough to pull a parent from alcoholism, it would Shuggie—a selfless, earnest, honest, boy whose optimism is exceptionally buoyant. Shuggie is nothing if not wholly dedicated to Agnes’ happiness, her survival. But then, every child of an alcoholic knows that even the most perfect daughter or son is no cure for the urge to drink. Anyone who’s watched their parent stumble through the door, slur meaningless yet wicked insults, reach for another drink while their child goes hungry in belly and soul knows they aren’t as important as the next bottle or can, who takes off their parent’s shoes mid-day and tucks them into bed—these readers will weep.And, at Shuggie’s side, like the coins he feeds and robs and feeds the electric meter, they’ll believe the promises to quit, hold out hope the AA will keep them clean, be the parent till the parent can gets back on his or her feet. The reader flinches at the blatant truths, and at the ‘skills’ with which Shuggie ‘survives’ ten years in the “new economy of the scheme”—the Eighties. Starved, neglected, abused, molested, and isolated, Shuggie wears his suffering on his jumper. But also, he knows Agnes doesn’t want to live like this.Stylistically, the omniscient narrator uses heavy metaphor to put images into context young Shuggie can understand. Every “like” and “as” at once clarifies otherwise ungraspable, while distancing Shuggie from reality. From the opening line—“The day was flat,” throughout the central “limpet” theme, onto the conclusion, where, “like a tugboat,” Shuggie nudges his friend’s shoulder, metaphor gives Shuggie a lens through which he can understand his world. And it is his world. Time is measured by plastic ponies and little green men.Stuart’s portrait—equally Shuggie’s and Agnes’—is imperfect. It’s sometimes rugged, always raw. But an exceptionally tight, polished tale wouldn’t make any sense. Readers who know the drink firsthand can relate. And those who are fortunate not to know the drink, they will forever see alcoholism differently. This is a story of empathy.

Trustpilot

5 days ago

1 month ago