Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

![The Skin I Live In [DVD] [2011]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/8129RKFm7bL.jpg)

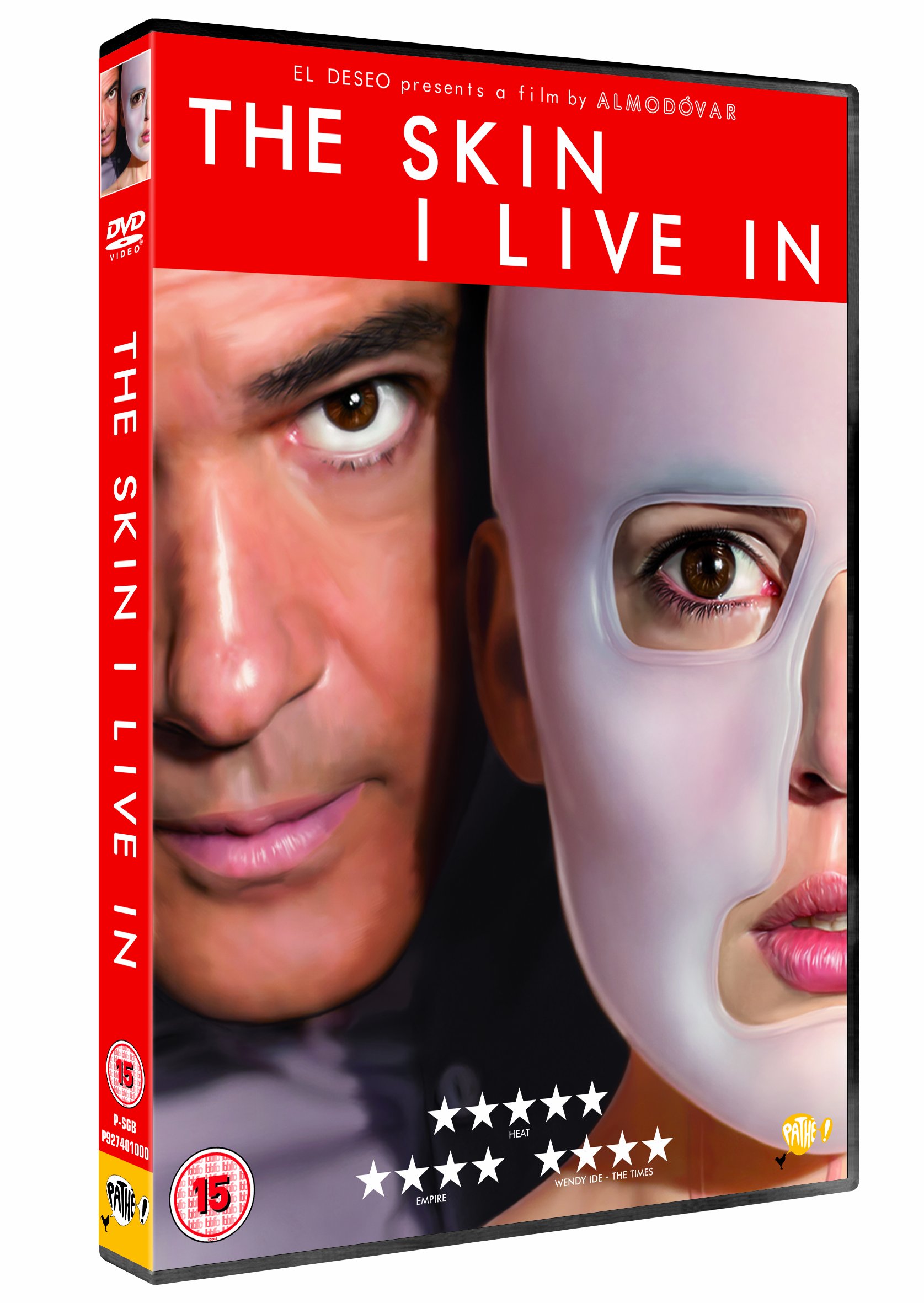

The Skin I Live In [DVD] [2011]

| ASIN | B004X9YNNO |

| Aspect Ratio | 1.85:1 |

| Best Sellers Rank | #135,610 in Movies & TV ( See Top 100 in Movies & TV ) #96,828 in DVD |

| Customer Reviews | 4.2 4.2 out of 5 stars (3,273) |

| Is Discontinued By Manufacturer | No |

| Language | Spanish (Dolby Digital 5.1) |

| Media Format | Color, PAL, Subtitled, Widescreen |

| Number of discs | 1 |

| Product Dimensions | 0.87 x 5.91 x 8.27 inches; 2.88 ounces |

| Release date | December 26, 2011 |

| Run time | 1 hour and 55 minutes |

| Studio | Pathé |

| Subtitles: | English |

F**F

An uncharacteristic cold genre exercise

Pedro Almodóvar’s 18th film The Skin I Live In (2011, La piel que habito) is by some distance quite the coldest film he has ever made. It is certainly admirable that a great director seeks to boldly change direction every now and then and Almodóvar has done it remarkably well twice before – with The Law of Desire (1987), the first of his sophisticated El Deseo films which broke with the wild transgressions of all his films prior to that; and with The Flower of My Secret (1995) which heralded a new satisfyingly weighty seriousness which marks the films now considered to be his greatest works, Live Flesh (1997), All About My Mother (1999), Talk to Her (2002), Bad Education (2004) and Volver (2006). Broken Embraces (2009) is less successful and perhaps signaled to the director the need for another new direction. He has acknowledged a nose-dive into darkness since the turn of the millennium and it is only the passionate investment of his own autobiographical obsessions and pre-occupations that glues the various shards of his always elaborate screenplays together to make satisfying wholes. That glue is completely missing from Broken Embraces and (given it is meant to be a romantic melodrama) is fatal in its effect. The glue is also absent from The Skin I Live In, but because it largely jettisons autobiography in favor of sci-fi psycho-horror the damage isn’t as great even if the effect is still cold and deadening. The film is not exciting enough, shocking enough, violent enough, or suspense-filled enough to satisfy as psycho-horror. It is also way too cerebral and clinical to satisfy as melodrama. A pastiche of different styles and genres, in one way it does absolutely feel like an Almodóvar film, but the frenetic plotting knitting together elements of Eyes Without a Face (1960, Georges Franju) with Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956, Don Siegel) and Rebecca (1940, Hitchcock) with Metropolis (1926, Fritz Lang) negates character empathy and finally leaves us chilled rather than touched. The film certainly is beautifully made and admirers of both Almodóvar and Antonio Banderas (making his return to the director after 20 years) will find ample compensations here. The following contains spoilers. The film relies heavily on a surprise twist so if you haven’t seen the film yet DO NOT read what follows.Taken from Thierry Jonquet’s novel Tarantula, The Skin I Live In is only the second of Almodóvar’s adaptations of someone else’s material (the first was his take on Ruth Rendell’s Live Flesh) and apparently had a decade-long gestation period. This dates the original conception to around 9/11 and as in much art made since then perhaps the dark negativity can be explained by Almodóvar reacting to outside contemporary events. Certainly it is his first film which is not obviously connected with Spain. A revenge thriller centering on the main theme of a mad scientist deploying transgenesis, the film is set in Toledo in Almodóvar’s home area of La Mancha, but it could be anywhere. The story centers on sinister plastic surgeon Robert Ledgard (Antonio Banderas) who is keeping a girl named Vera Cruz (Elena Anaya taking full advantage of Penélope Cruz’s pregnancy) in a room on his country estate El Cigarral under laboratory conditions and with the help of his mother Marilia (Marisa Paredes).The plot concerns how Vera came to be in the room and how she escapes. As per usual with Almodóvar the narrative is complex and is teased out a-chronologically through flashbacks, dreams and unlikely melodrama. In a nutshell, Ledgard has lost both his wife Gal and his daughter Norma (Blanca Suárez) to separate suicides. Gal was a burn victim from a car crash who later threw herself out of a window when she caught sight of her hideous reflection. Norma had been witness to this and was recovering from the trauma induced by it when she was sexually accosted at a party by local fashion boutique salesclerk Vincente (Jan Cornet). The experience renewed her trauma which in turn led to her following her mother out of a window. In the film’s present Ledgard devotes his life to two passions – to research and produce a new human skin that resists burns, and to punish the man who effectively sent his daughter to her early death. So he kidnaps and experiments on Vincente. The twist is that as well as developing a new skin, he also changes Vincente into a girl. He gives him hormone therapy, a vaginoplasty and breasts. But he doesn’t change him into just any girl. He changes him into the very image of his dead wife Gal. This causes trouble for when Ledgard’s half-brother Zeca (Roberto Álamo) comes to visit his biological mother Marilia he mistakes Vera for Gal and rapes her thinking he is meeting again the woman with whom he was having an affair when they both had their car crash. Also, Marilia’s maternal jealousy is aroused when Ledgard later allows Vera to take care of him. Trapped inside the body of ‘Vera’ Vincente however has been spending the time desperately trying to cling on to his identity and he eventually gets the chance to escape by shooting both Ledgard and Marilia dead. The film finishes with Vincente returning to his mother’s shop and declaring his identity through Vera’s body.Gender-bending has long been the preserve of Almodóvar, a director born out of the transgressive Movida Madrileña artistic renaissance after the death of Franco in 1975. Having built a career out of attack (on Francoism) and celebration (of democracy) in films which center on transience and identity-search in three different areas (politics/society, the human body/sexuality and of the artistic creative impulse itself [story-telling, cinema history and a very knowing postmodernism]), transsexuality (the desire for authenticity to “resemble who you’ve dreamed you are” as voiced by Agrado in All About My Mother) is the very expression of a freedom denied to Spanish people for 40 years of Francoist rule. The depressed world atmosphere post-9/11 coupled with a down-turn in the fortunes of the Spanish economy perhaps lie behind Almodóvar’s decision in The Skin I Live In to treat gender-bending as a punishment rather than an expression of freedom. In the same way all the other ‘freedoms’ gained with the 1977 General Election prove to be illusory to reflect the sobering fact that most people in Spain were better off under Franco than they were three decades later.Gender-bending is presented as a negative trapping mechanism as is sex itself. Of the three couplings we see in the film two are rapes (Zeca on Vera and then Vincente on Norma). The third is also incredibly cold. From Ledgard’s point of view sex with Vera/Vincente amounts to necrophilia with the image of his dead wife while from Vincente’s point of view sex is a necessary thing to win Ledgard’s trust so that he can kill him. The oppressive control characters seek to effect on each other through sex here is a far cry from the positive sexual liberation of a film like Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! or the later Live Flesh.Along with sex, drugs stop being the expression of liberty they were in early Almodóvar and become the tools of use and abuse. Ledgard is the mad scientist who uses drugs to effect his weird schemes. He shoots Vincente with a tranquilizer gun, drugs his food, sedates him for the sex change operation, develops his new skin by using transgenesis-related chemicals and then administers hormone therapy to grow breasts and feminize Vincente completely, trapping him within a woman’s body. Furthermore, it is under the influence of speed that Vincente loses control of his actions at the party and attempts to sexually assault Norma. Norma is also under the influence of drugs. This is a point highlighted by a conversation between the two where they misunderstand each other. Vincente says he is on drugs and asks Norma if she is too. She is under her father’s medication for her trauma-related depression and so she says, “Yes.” Social drugs are thus equated with drugs meant for medication and are shown by Almodóvar to be equally sinister. The only drug we see as innocently ‘recreational’ is Ledgard’s opium pipe which significantly he never gets to enjoy even though he tries twice to do so. Again this is a far cry from a film like Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! where Marina falls in love with Ricky partly because he goes out on the streets to score heroin for her!Looming over the twisting of once-positive freedoms into something altogether more sinister is the ice cold depiction of middle class Spanish society we are offered in the film. The General Election promised freedom for all, but the end result 30 years later is the tyranny of the haute bourgeoisie over those beneath them on the social scale, especially in this film the petite bourgeoisie as represented by Vincente’s family shop. Almodóvar dwells on the effect Vincente’s abduction has on his mother (Susi Sánchez) as she frantically tries to get the police interested in her son’s disappearance. We see the haute bourgeoisie in sophisticated social gatherings, especially at a party where Ledgard talks to the un-named president of the bio-tech institute (José Luis Gómez) about the ethics of transgenesis and then at a sumptuous society wedding where it is emphasized that expensive medical research has been carried out merely to make the rich look better through cosmetic surgery rather than to help plain ordinary people. Furthermore the film offers the idea of the rich making themselves beautiful through the use and abuse of those further down the scale. Vincente is to an extent a social victim and slots alongside a number of other characters in Almodóvar films (Antonio in The Law of Desire, Ignacio, Juan and Enrique in Bad Education) who are trapped in a rural environment yearning for escape – the very situation of Almodóvar himself in the late 1970s. Interestingly, this idea receives even clearer expression in Almodóvar’s next film I’m So Excited! in which a plane is offered as a metaphor for Spanish society about to crash with economy class passengers knocked out by drugs while the first class passengers hedonistically party on throughout the night.Transience and identity search usually plays out in Almodóvar in the arena of artistic creativity with a discourse on postmodern themes, but in this film this is muted. There is no metafiction, no faction, no narrator debate, no creator doppelgängers for Almodóvar and little meditation on the artistic process. To maintain his sanity (to insist his identity) Vincente takes to writing and drawing on the walls of his cell and to the making of papier maché figures based on a Louis Bourgeois book. It could also be argued that Ledgard is a plastic surgeon artist creating new bodies through unethical experimentation on humans. The only aspect of postmodernism to be fully present is the serial referencing to other films. Usually in Almodóvar these are cleverly bedded into the narratives to hugely positive effect (Jean Cocteau’s La Belle at la Bête in Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, Ingmar Bergman’s Autumn Sonata in High Heels, Joseph Mankiewicz’s All About Eve in All About My Mother, Luchino Visconti’s Bellissima in Volver, Almodóvar’s own Shrinking Lover within Talk to Her), but in The Skin I Live In the references are all negative ones to films which stress man’s manipulation of fellow man and an underlying desire for megalomaniacal control. The main reference point is Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face which features a another mad scientist this time prowling the streets at night for victims who will supply him the skin he needs to repair his daughter’s face. Then there is Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers which was a 50s allegory on an alien force (it could be either communism or fascism) taking over the bodies of innocent Americans. Hitchcock’s Rebecca also provides very obvious reference points – the spirit of the dead wife hovering over the house of the bereaved husband, the suicide by jumping from a second floor window which Joan Fontaine almost does, but which both Gal and Norma actually do, the Mrs. Danvers-like omnipresence of Ledgard’s mother Marilia who jealously cares for her son and resents Vera’s ‘help.’ Most sinister of all perhaps is the base reference to Fritz Lang’s Metropolis with Ledgard playing Rotwang as he brings his wife back to life in the shape of somebody/something else. Here the wife is named Gal and changed by Ledgard into Vera Cruz (a reference to Robert Aldrich’s 1954 Western of the same title in which Sara Montiel [Almodóvar’s childhood cherished movie idol who he famously brings back to life in the part-autobiographical Bad Education] plays the love interest). In Metropolis the wife is named Hel and changed by Rotwang on Joah’s command to Maria, the evil copy of a Messiah figure who manipulates a whole city to destruction.The purpose of serial referencing to other works of art within a postmodern text is usually to acknowledge what has gone before and build on it afresh and in Almodóvar’s best films there is a wonderful feeling of the old ingredients of cinema being shaken up and taken in a new direction, to an exotic place which hasn’t been essayed before. This is most effective when he pushes social/sexual taboos to their very limits (eg; sexual abduction in Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, rape in Kika and Talk to Her, incest in Volver) to approach uncomfortable truths which scarcely get voiced in mainstream cinema. In The Skin I Live In the referencing doesn’t succeed in doing this. Indeed, it serves to confine the film within the bounds of what has already been done. Not only has the Frankenstein mad scientist theme been done to death elsewhere, it has been done much better by the various filmmakers I identify above. This makes the present film little more than an academic exercise even if the acting and José Luis Alcaine’s photography (showcasing the extraordinary production designs of Antxón Gómez – check out the interiors of Ledgard’s house!) combine with a polished script to make a fine aesthetically appealing end product. Special mention should also be accorded to Alberto Iglesias and his wonderful music score seguing from Philip Glass-like violin ostinatos to tranquil piano most effectively. The coldness on display here can be justified by Almodóvar’s concern with present day Spanish society skating perilously close to disaster in a gloomy post-9/11 world and the way he has twisted his usual themes to take this on-board is admirable in a way, but I for one see the world of Almodóvar as being fundamentally warm and full of positive things to say about the human condition. That seems to be a million miles away from The Skin I Live In which I hope will quickly become more ‘The Skin He Lived In’ as he moves on snakelike to things altogether more positive in the future. I’m So Excited! is superficially more positive even if the view of Spanish society remains bleak and we must wait and see if the upcoming Julietta will lighten the gloom even further.The quality of this DVD release is outstanding, the visuals (aspect ratio 16:9 Widescreen 1.85:1) bold and clear and the sound (5.1 Dolby Digital) bright and transparent. There are no extras worthy of note outside a brief montage of production images and a short interview with Almodovar and Anaya given before the film’s 2011 premier at Somerset House, London, both speaking in English.

D**R

'The Skin I Live In' will tease and entertain you through to the perverse end.

Antonio Banderas is reunited with Spanish director Pedro Almodovar, who made him famous in his early films such as the hilarious 'Time Me Up, Time Me Down'. Banderas plays Robert Ledgard, a highely regarded but controversial cosmetic surgeon. Ledgard lives with his housekeeper Marilia (Marisa Paredes), and the mysterious Vera (Elena Anaya) who seems to be imprisoned, spending her days dressed in a skin-tone bodysuit.Almodovar keeps you guessing right from the beginning, and Vera is the most intriguing, is she Ledgards patient, perhaps his daughter or even his wife? An intruder initiates a change in Ledgard and Vera's relationship. The story unfolds through numerous flashbacks involving Ledgard's daughter and Vicente, who both met at a party, establishing the nature of Ledgards actions to come.Ledgard is haunted by his wife's severe burns following a car accident, he becomes obsessed with healing her, working day and night on skin tissue experiments. Ledgards obsession pushes him to experiment with `transgenesis' - an illegal form of genetic engineering on humans.Not only does the plot keep you guessing but you keep asking yourself 'is this a horror movie, a revenge thriller, a dark comedy or a suspense thriller?'. In fact it's all of these and much more.The incredibly beautiful Anaya is a fantastic foil to Banderas, growing in her role and gaining greater significance and complexity as the film unravels, and it is she as Vera who defines the film. Banderas is a charismatic lead, every inch the Spanish Cary Grant, stylish and charming, but with an unnerving menace. You can even empathise with Banderas' humanistic portrayal of Ledgard, traumatised by his pain and loss. You do, until <em>that</em> moment!Staple Almodovar themes of identity, flesh, sex and power are all present, but it's the quite ridiculous twist which completes this film. You soon realise this cruel joke has depth, and very real implications, not least the premise of the act of male aggression and penetration, sexual or otherwise.There are several cinematic references and homages throughout this film but Almodovar still manages to make 'The Skin I Live In' all his own, this absurdly twisted psychological horror could not have been directed by anyone other than Almodovar.Almodovar's films are renowned for their twists and absurdities, plus a healthy dollop of comedy and kitsch, but nothing as sinister and altogether bonkers as 'The Skin I Live In'. The brilliance of Almodovar is his ability to normalise the odd and the absurd, 'The Skin I Live In' will tease and entertain you through to the perverse end.

Trustpilot

2 months ago

1 month ago