Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

Desert Online General Trading LLC

Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Full description not available

P**N

Wonderful exposition of the foundations of Curvature and Connections

This book is the second volume of the 3rd edition in a five volume series on differential geometry. The focus here is on the foundations of curvature and connections.The only prerequisite for volume II is a careful study of volume I. In particular, you'll need a good understanding of the Riemannian metric and you'll need to be comfortable with manipulating differential forms. Also pay attention to the differential equations material used to establish Frobenius Integrability in Chapter 6 of volume I. In addition, you'll need the main concepts from the Lie Groups study of Chapter 10 of volume I.The author begins the study of curvature with a review of the classical theory of curvature of curves and surfaces in Chapters 1 and 2. These chapters are written in style that helps the reader anticipate more general results for Riemannian manifolds. For example, the reader will notice the rotation index of a planar curve can be represented in terms of its total curvature; a result which foreshadows the Gauss-Bonnet Theorem. Both Euler's Theorem and Meusnier's Theorem for surfaces embedded in Euclidean 3-space are studied.Chapter 3 details the geometry of surfaces as developed by Gauss. Spivak's treatment here is very unusual, and, in Part A of this chapter, the author actually gives an English translation of original paper of Gauss. Reading this is a bit unusual as the author alternates the translation of Gauss on a page with comments by the author on the preceding page. Part B of the chapter gives the accounting of the Gauss Theory in modern notion. Part B is delightfully geometric and includes all of the 'greatest hits' from the theory, including the Theorema Egreguim and the Triangle Excess Theorem.Chapter 4 studies Riemann's theory of curvature of manifolds, and contains 4 parts. Part A and Part C are English translations of Riemann's foundational work, while Part B and Part D cast this work in the light of more modern notion. Riemann's curvature tensor is built up from an intuitive study of the second-order terms in the Taylor series expansion of the Riemannian metric. The author also introduces what he calls the "Test Case" for curvature theory: Flat manifolds are locally isometric to Euclidean space. Spivak uses this "Test Case" repeatedly throughout the remainder of the text to reinforce the various notion of curvature as he studies the work of Riemann, Ricci, Kozul, Cartan and Ehresmann.Chapter 5 (the Debauch of Indices) studies the work of Christoffel and Ricci in developing the covariant derivative. The aim of this work is to simplify the somewhat cumbersome formulas for Riemann's curvature tensor. The reader quickly sees that effort, called absolute differential calculus, is not altogether successful and leads to an veritable explosion of multi-indexed quantities and even harder-to-penetrate formulas. Clearly a better way is needed if we are to move forward with our study of differential geometry.The "way forward" is Kozul's concept of the connection and this is introduced in Chapter 6. First, note that the connection here is one of the versions of the introduced by Kozul as a map of pairs of vector fields to a vector field. Another useful version, not studied in volume II, is to consider the connection as a Hessian which maps any smooth function to a bilinear form on the tangent space. Second, note that Chapter 6 is usually the starting point for most treatments of curvature in differential geometry (e.g Do Carmo's "Riemannian Geometry"). Without the motivating material from the previous chapters, it would be difficult to understand the need for(or the point of) Kozul's connection.Cartan's theory of curvature via a study of moving frames is detailed in Chapter 7. The author is careful to intuitively motivate Cartan's deviation from Euclidean concept as represented in the structure equations. Cartan's curvature tensor is shown to agree with Riemann's tensor, the "Test Case" is revisited, and the well-known fact that the curvature determines the Riemannian metric is established.Building on the orthonormal frames from the previous chapter, Spivak now considers Ehresmann's theory of connections in principal bundles in Chapter 8. The main results here introduce the Ehresmann connection on the frame bundle, and gives the Kozul connection as a Lie derivative, thought of as the Cartan connection obtained from the Ehresmann connection.My only complaint is that the author didn't include any exercises in this second volume. This is a real shame as the exercises in the first volume were very well-designed and one of the highlights of that text.

E**Z

a classic

This was one of the books that helped me decide to get a phd in math (even though I didn't officially study differential geometry). Spivak's books read like chalkboard lectures by a superb lecturer. The treatment of curvature of curves and surfaces in the first two chapters are really good. I am still absorbing the meat of the book (Riemannian geometry) and I have been reading it on and off for 20 years.

C**R

What can one say about Spivak's books on differential geometry ...

What can one say about Spivak's books on differential geometry. I used a complete set in my undergrad years and used them so much that I wanted a new copy! Definitely one set of books worth having in every mathematician's library.

Q**2

Five Stars

These are classics

A**N

Curvature, tensor calculus, connections, moving frames, fibre bundles

For me, Volume 2 is the most useful of Michael Spivak's 5-volume 1970 DG book series because it presents connections for tensor bundles and general fibre bundles, whereas Volume 1 presents only differential topology (i.e. DG without connections or metrics) and some Riemannian geometry and Lie group geometry.Perhaps the most notable part of Volume 2 is the bold attempt on pages 336-341 to create a kind of Rosetta stone to translate between 5 popular formalisms for affine connections. There are a few more formalisms for connections (both affine on tangent bundles and more generally on ordinary and principal bundles). So this Rosetta stone needs a few more languages now! It seems to me that the author's bold attempt fell short of the objective, but very few other authors have even made the attempt, at least in published textbooks.Volumes 3, 4 and 5 are applications of the basic theory from Volumes 1 and 2 to the development of theorems for particular areas of pure mathematical DG, as opposed to the physicists' DG in cosmology and gauge theory. This 5-volume series is very distinctly aimed at pure geometry applications, which explains why there is almost nothing about pseudo-Riemannian geometry here, and not very much (although there is some) about pull-backs of connection forms from principal bundles to the base-point manifold. In fact, several gauge theory books refer to Volume 2's treatment of principal bundle connections in Chapter 8 (pages 305-349), which gives much of the DG background needed for gauge theory. The lack of explicit applications to gauge theory by Spivak is unsurprising because it was only in about 1975-1977 that the lecture series of Drechsler and Mayer brought to general attention the fact that gauge theory in particle physics is an application of connections on fibre bundles.Chapters 3 and 4 of Spivak's Volume 2 present some much-needed historical explanation of how the modern abstract DG concepts evolved. However, having read some of this translated material by Gauss and Riemann in the original Latin and German myself, I'm not really convinced that there is a continuous evolutionary line of history from their ideas to the late 19th century developments in tensor calculus which led to the absolute differential calculus and Levi-Civita's notion of parallelism, which really came alive due to applications in general relativity and gauge theories. Even with Spivak's explanations of the meaning of these works by Gauss and Riemann, the significance for modern pure DG and applications to physics seems tenuous. Nevertheless, it's good that Spivak did make this attempt to trace modern DG ideas to the early and mid 19th century.Chapters 5, 6 and 7 on the Ricci calculus, the Koszul connection and Cartan's repère mobile are widely applicable in physics as well as pure geometry. There is so much literature which uses these approaches, there is no choice but to understand them. So this is all good value.Chapter 8 introduces for general principal bundles some general concepts of connections, such as the Ehresmann connection and horizontal lifts, but the author very quickly abandons the general principal bundle context and reverts to the very special case of principal tangent bundles which correspond to Cartan's moving frames. This is unfortunate, but it was not generally known in 1970 that connections on general PFBs would assume such great importance in quantum field theory.The Spivak 5-volume DG book series is so widely cited in the literature, it makes sense to have at least Volumes 1 and 2 on the bookshelf to check up on the citations. However, I would not personally regard these two volumes as an adequate introduction on their own to modern DG concepts. The author's presentation in these books (as opposed to his crystal clear 1967 calculus book which I learned calculus from) is not quite tidy enough for a first introduction, but it is a valuable complement to all the other DG books out there.By the way, I bought all 5 volumes of the 1999 third edition in 2002 directly from Publish or Perish.

M**K

not dead yet.

Volume 2 is not dead, but is in a somewhat long recovery. Should be available from the publisher in a couple of months or so.

M**M

One Star

Mr Spivak manages to slaughter a beautiful topic in math by being unable to explain the topic properly.

B**I

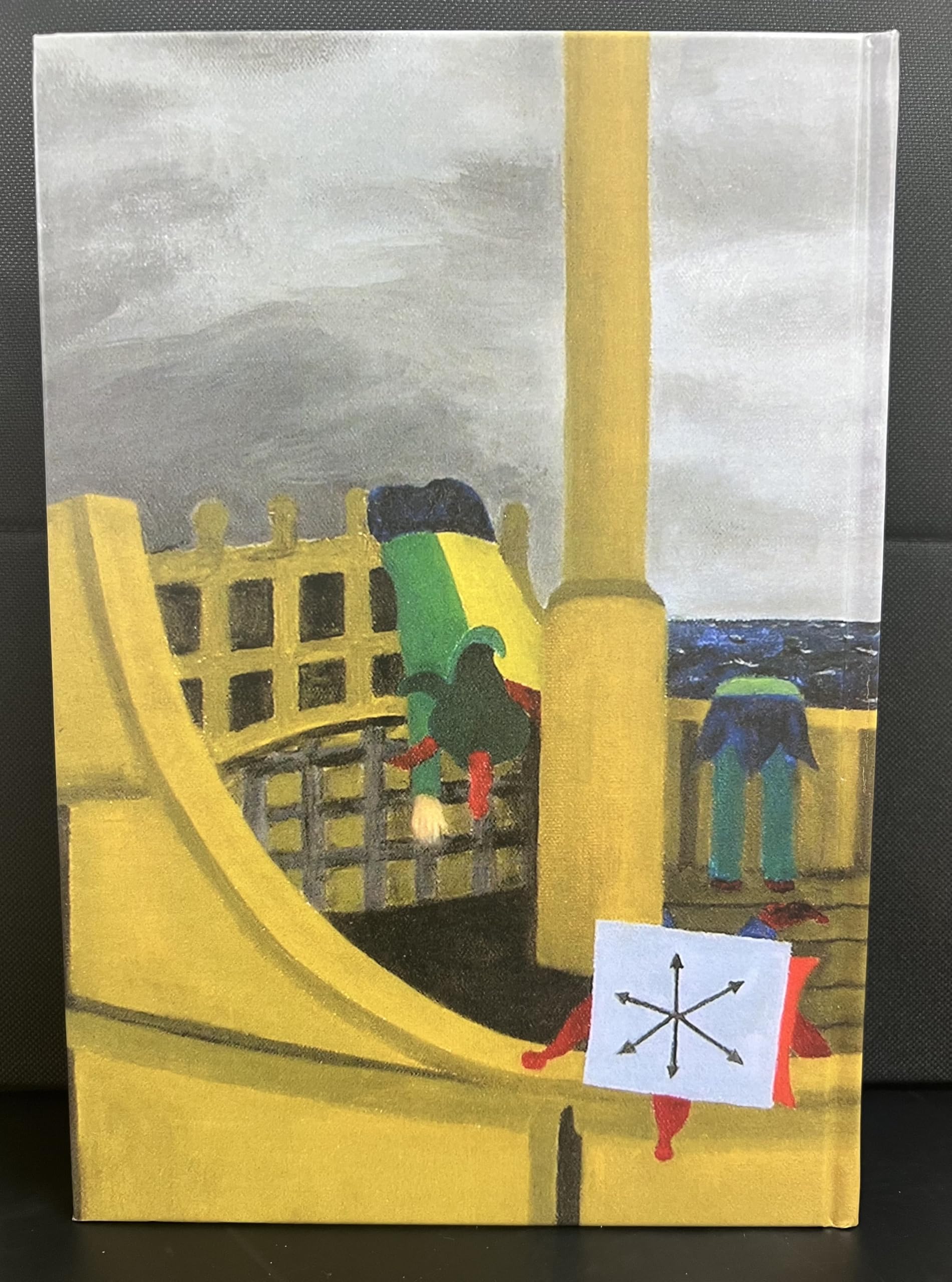

A Comprehensive Introduction to Differential Geometry, Vol. 2, 3rd Edition

Hours of reading fun! Well paced and twice the fun of Volume 1. Michael does it again! A spellbinding thriller from cover to cover. You gotta love it.

Trustpilot

2 months ago

1 week ago